SUMMARY

In the wake of the Second World War, Citi sought to promote its contribution to economic and business expansion through specially commissioned artworks. The advertising campaign ran for many years, while the art’s appeal endures to this day.

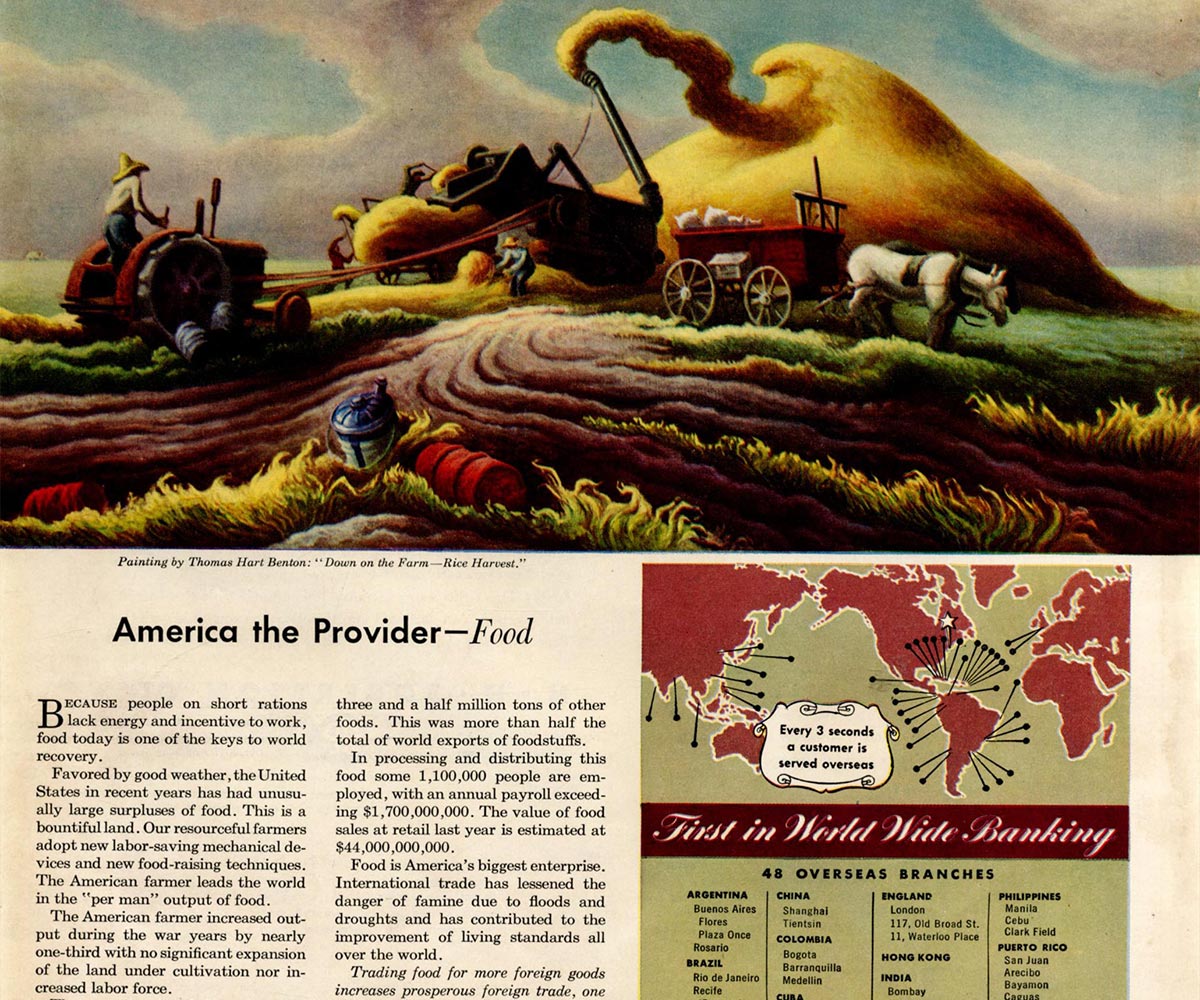

In the aftermath of World War II, Citi commissioned art as the centerpiece for a new print advertising campaign.1 The aim was to promote our organization – in its then-incarnation as the National City Bank of New York – as an enabler of commerce and infrastructure development. The full-page ads appeared in national publications, including Fortune, Time, Newsweek, and Town & Country.

The accompanying text addressed “big picture” issues such as the US’s contribution to global food supplies, the state of the nation’s waterways or the significance of early bookkeeping machinery. Citi’s related services were mentioned only briefly in closing. The campaign would ultimately see 42 artists create 126 paintings in a variety of styles. Among the best-known artists engaged were Thomas Hart Benton and Charles Sheeler.

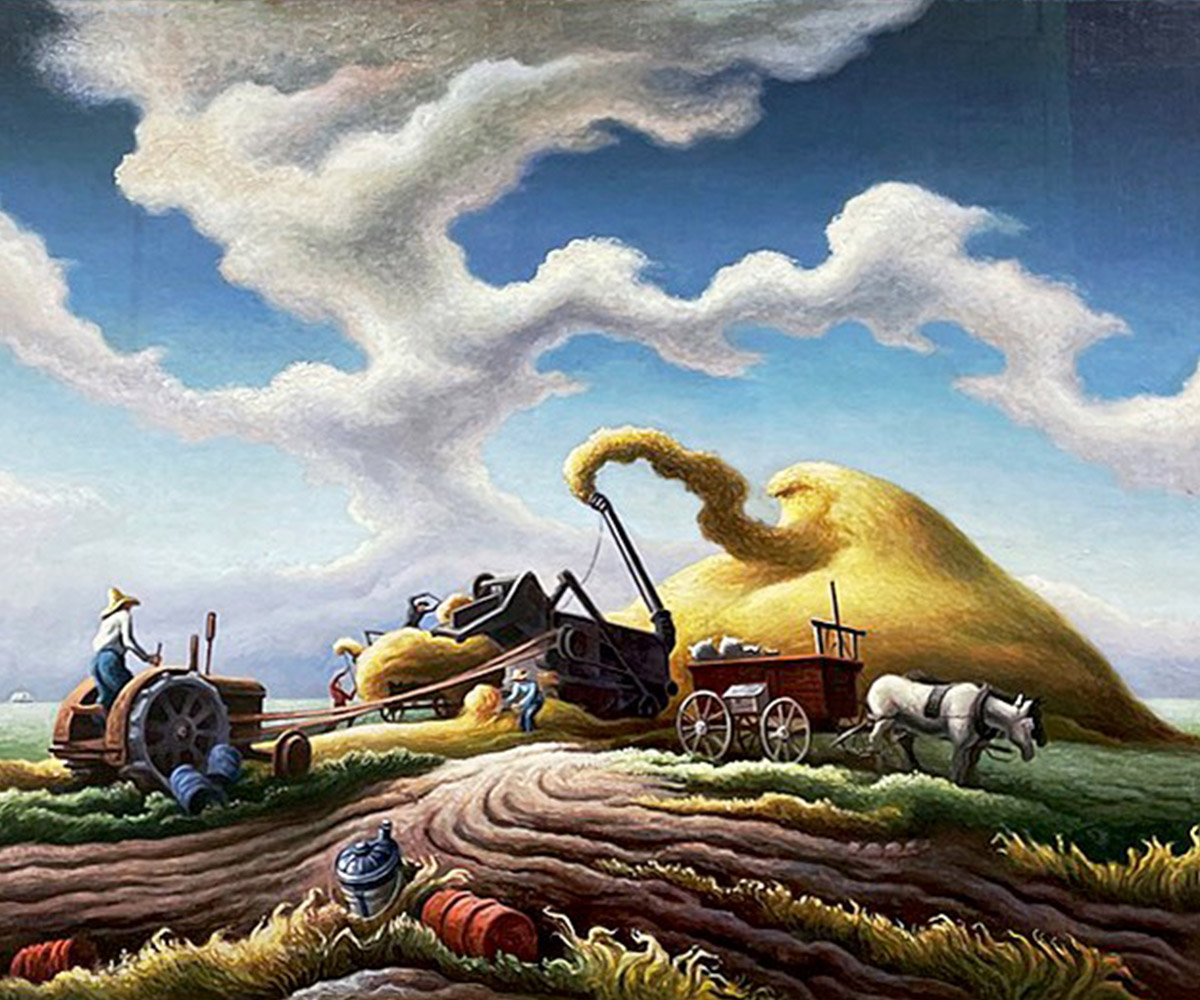

The National City Bank of New York. “America the Provider – Food.” Advertisement.

Fortune, January 1948; Time, January 1948.

Thomas Hart Benton was established as a leading Regionalist painter when he was hired. His self-portrait had appeared on the cover of Time magazine, and institutions including the Whitney Museum and the New School for Social Research hired him to create large-scale murals.2

When teaching at the Art Students League in New York, Benton was an influential instructor of younger painter Jackson Pollock. His father and grandfather were Missouri’s US representative and senator, respectively, and Benton had first-hand knowledge of local industries. His work frequently celebrated workers in the region’s farms, steel mills, and coal mines.

Dawn on the Farm, Rice Harvest, circa 1945

Thomas Hart Benton, American 1889 – 1975

Depictions of rural America were hallmarks of Benton’s work. It was therefore apt that he was commissioned to paint Dawn on the Farm-Rice Harvest, to illustrate an ad highlighting America’s global leadership in food production. Typical of his approach, the brushstrokes bend and wind across the composition. The shape of the mound of harvested rice is reflected in the clouds, the dirt tracks, and even the tractor driver’s hat.

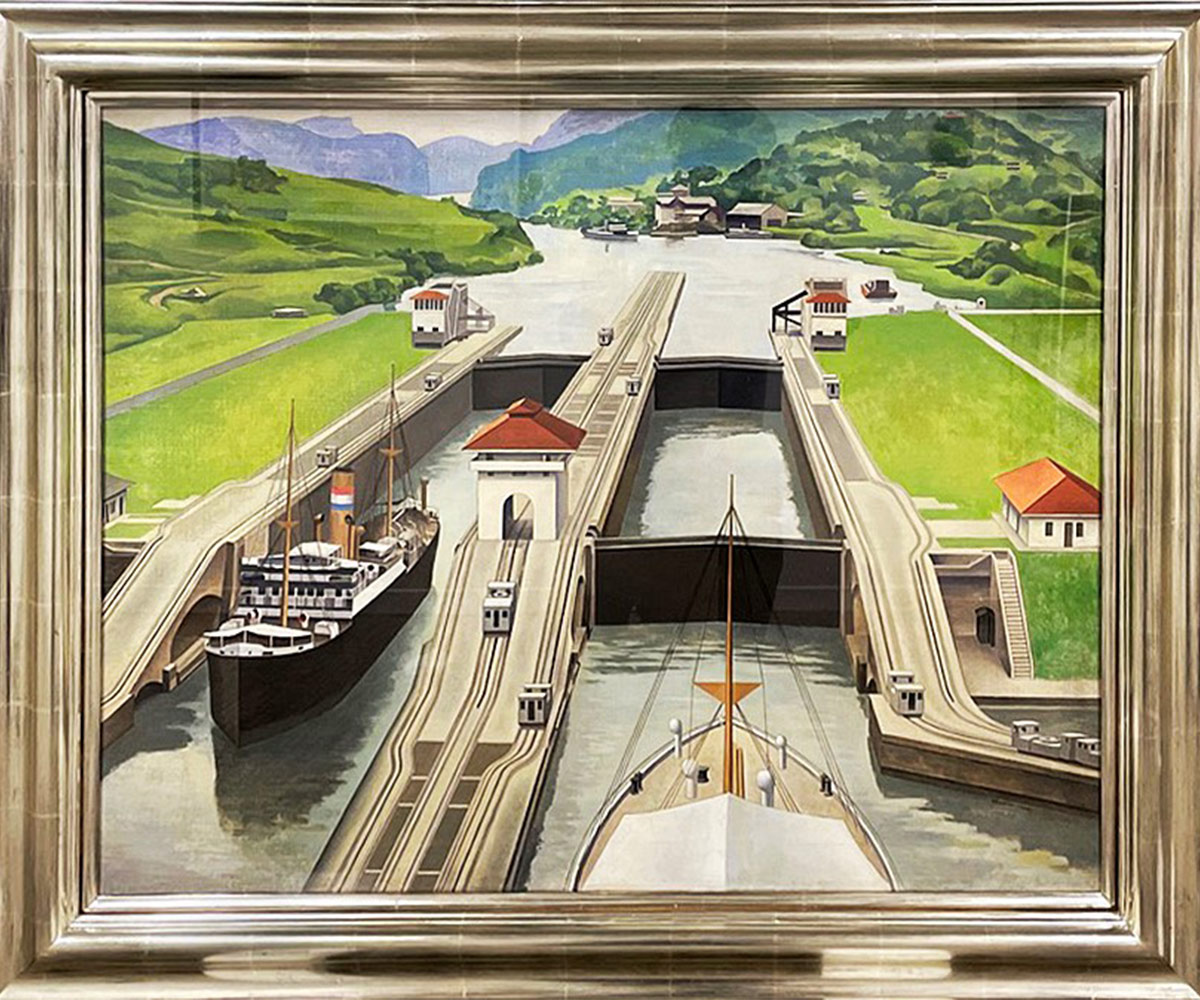

Unlike Benton, Charles Sheeler probably did not have direct experience of his subject for the campaign. For his painting of the Panama Canal, he likely worked from photographs of the waterway and may have drawn from the studies of Boulder Dam - renamed Hoover Dam in 1947 - that he had created a decade earlier.3

In his painting, the canal at Gatun Locks is composed with a wildly tall perspective and non-naturalistic scale. The ship on the right, whose bow is visible, is far larger than the vessel on its left. In life, both would have been of comparable size. This work shares qualities with his enigmatic The Artist Looks at Nature (1943), held in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.4 In both paintings, the artist incorporated a tipped compositional perspective and included high walls and broad, flat green planes.

Riding Through Pedro Miguel Locks, Panama Canal, 1946

Charles Sheeler, American 1883 - 1965

Throughout his long career, Sheeler oscillated between photography, film, painting, and printmaking. He regularly took on commercial projects, from architectural photography in the 1910s, to fashion photography for Condé Nast, to promotional photos for the Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge plant, to illustration for periodicals, including Fortune. By the 1940s, his work was held in museums including the Whitney, and he had exhibited widely, including at the influential Armory Show of 1913 and multiple times at the Museum of Modern Art.

Among the other artists whose work appeared in National City Bank of New York’s series were Rockwell Kent, Reginald Marsh, Walter Murch, John Atherton, and Clarence Carter. The bank engaged the agency Batton, Barton, Durstine & Osborne (BBDO) for the project. In turn, BBDO coordinated with Associated American Artists (AAA), an organization that popularized contemporary art through sales of low-cost prints and connected artists with commercial projects.5

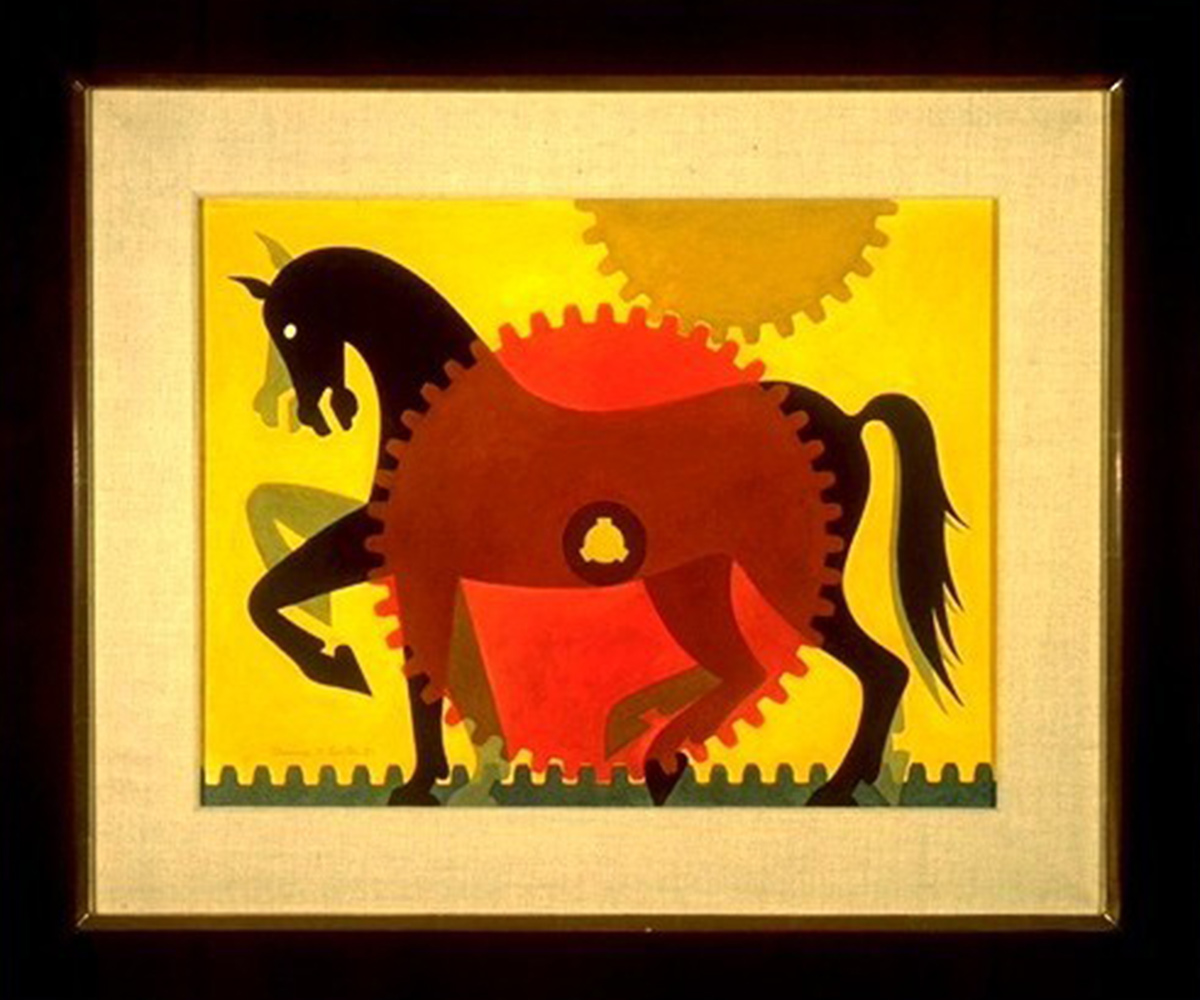

Some of those commissioned had established careers as “fine artists,” while others including Clarence Carter had worked more often in illustration or other work for hire. Commissioning records describe the great freedom the artists had in how they chose to address their subjects. Carter, for instance, painted machinery by superimposing interlocking gears over the silhouette of a horse – a simple but elegant representation of horsepower.

Horsepower, 1951

Clarence Carter, American 1904 - 2000

Although the ads ran in popular magazines, the intended audience wasn’t necessarily the general consumer. Instead, the ads were meant to appeal to corporate executives who might seek out the banking and financing services of the National City Bank of New York.

The campaign lasted fourteen years, an extraordinary run for any marketing initiative. During that time, our organization had a succession of three CEOs, began construction of a new global headquarters, and acquired a new identity as The First National City Bank.

While more than half a century has passed since the final ad appeared, the campaign’s art retains its captivating grace. We are proud of this chapter of our heritage, our enduring association with art, and our continuing role as an enabler of global growth and progress.